……..Why Trinidad and Tobago Must Act Now?

By Corneilus George

Across Europe, a decisive shift is underway in how governments protect children in the digital age. Age-verification laws, limits on social-media access for minors, and firm school-day smartphone controls are no longer fringe proposals; they are rapidly becoming mainstream public policy, framed not as censorship but as learning protection and mental-health safeguarding.

The question for Trinidad and Tobago is no longer whether such measures are controversial. The real question is whether we can afford not to act while the evidence and the world move ahead without us.

For years, digital access was treated as an unquestioned good. Connectivity meant opportunity, information, and participation in the modern economy. But the social experiment of unrestricted childhood exposure to algorithm-driven platforms has now run long enough to reveal its costs.

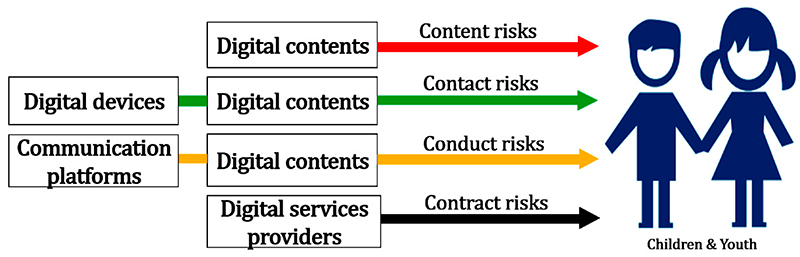

Rising anxiety, sleep disruption, cyberbullying, exposure to predatory behaviour, and declining classroom focus are no longer anecdotal concerns; they are recurring patterns documented across multiple societies. Europe’s tightening regulations signal a growing global consensus: children require guardrails online just as they do offline.

Trinidad and Tobago stands at a familiar crossroads, aware of the risks, yet hesitant to move from discussion to a decisive framework. We already recognize the dangers of online exploitation and harmful content. Schools struggle daily with smartphone distraction. Parents feel increasingly powerless against platforms engineered to capture attention.

Yet our policy response remains fragmented: guidance without enforcement, awareness without accountability, and concern without structure. In a digital environment measured in milliseconds, delay is itself a decision and rarely a protective one.

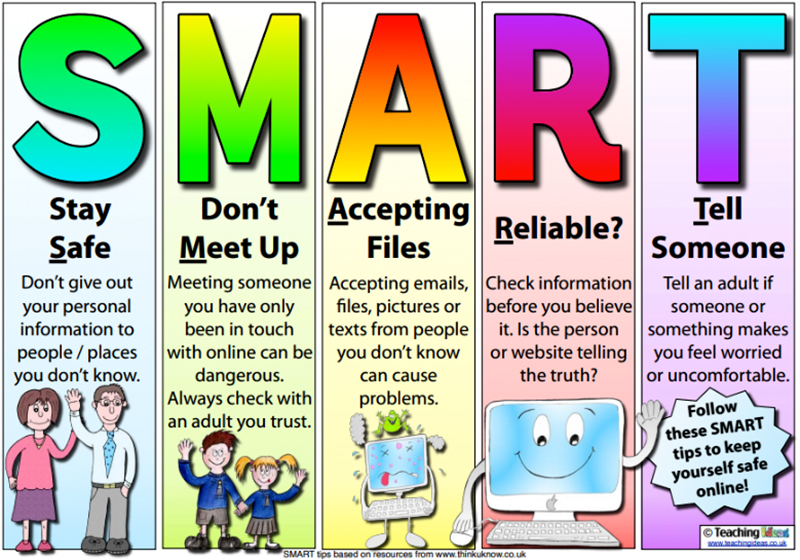

A robust Child Online Safety Framework is what is required; it would not mean isolating young people from technology. On the contrary, it would ensure they can benefit from digital learning, creativity, and communication without being exposed to preventable harm.

The goal is balance, not prohibition; protection, not panic. But balance requires architecture. It requires law, regulation, education, and enforcement working together rather than in isolation.

Firstly, Trinidad and Tobago must establish clear age-appropriate access standards for high-risk online platforms. Age limits already exist in theory across many services, yet without credible verification, they function as little more than polite suggestions.

Reasonable, privacy-respecting verification mechanisms, combined with legal responsibility on platforms to enforce them, are essential if age rules are to mean anything at all.

Secondly, we need stronger institutional coordination. Child online safety cannot sit solely with schools, parents, or police. It demands an integrated system linking education authorities, telecommunications regulators, child-protection agencies, and law enforcement, supported by clear reporting pathways and rapid response protocols. Protection delayed is protection denied.

Thirdly, schools require nationally consistent smartphone policies that prioritize learning time and mental well-being. Europe’s experience shows that firm, simple rules, such as bell-to-bell restrictions with limited educational exceptions, reduce conflict, restore classroom focus, and support healthier social interaction among students. Trinidad and Tobago already debates this issue; what is missing is uniformity and resolve.

Fourthly, any serious framework must invest in digital literacy for both children and parents. Regulation alone cannot outpace technology. Young people must understand manipulation, misinformation, privacy risk, and online exploitation. Parents must be equipped to guide rather than merely react. Education remains the most durable form of protection.

Critics will warn of overreach, censorship, or technological pessimism. These concerns deserve consideration, but they cannot justify inaction. Every major advance in child protection, from seatbelt laws to anti-smoking rules, faced similar resistance before becoming common sense. The digital environment should be no different. Freedom without safety is not freedom for a child; it is exposure.

The wider world is moving with urgency because the stakes are now unmistakable. Childhood itself is being reshaped by technologies that did not exist a generation ago. If Trinidad and Tobago hesitates too long, we risk importing not only the benefits of the digital age but also its deepest harms, without the safeguards others are already building.

A robust Child Online Safety Framework is therefore not merely a regulatory exercise. It is a statement about national priorities. It declares that innovation must coexist with protection, that education must prevail over distraction, and that the well-being of children outranks the convenience of unchecked digital access.

History will not ask whether we debated the issue thoroughly. It will ask whether we acted in time.